Eightfold’s Lawsuit: A Wake-Up Call for Talent Acquisition

Nothing ever really happens in HR Tech. Not objectively, anyway. Sure, the messaging and product marketing might change, and there might be some M&A or funding activity impacting the ecosystem.

Most of this is esoteric inside baseball that has little to no relevance to the overwhelming majority of recruiting end users, or the candidates they’re hoping to hire.

It’s a lucrative but arcane little niche that’s oversaturated with emerging technologies positioning themselves as “challenger” brands, which is kind of cute, considering that legacy ERPs have such a disproportionate share of the HR Technology market.

The space thrives on stasis and monetizes the status quo, save for a steady drip of product announcements, “AI powered” pitch decks that all look and sound pretty much identical, and LinkedIn posts insisting that this time, it’s different.

It’s always the same shit, of course – but optics are everything in recruiting, really. This is why startups in the space generally spend more on SG&A than R&D, after all.

But then again, once in a very long while, something momentous happens, with significant repercussions for companies and candidates alike; these blue moon events do, decidedly, drive widespread changes in how companies find workers, and how candidates find companies.

Most of the time, these seminal, seismic shifts follow a pretty predictable pattern, even if no one sees them coming.

It all starts when the legal system and the talent acquisition ecosystem collide. Lawyers, as you may know, don’t really care about category positioning, product roadmaps or integration partners.

They do care about compliance – and often, when attorneys dig into the intersection of hiring and technology, they don’t see “innovation” – they see a lot of potential violations. And, inevitably, they’re forced to ask one of talent technology’s most enduring questions:

Is this even allowed?

The answer is often up for interpretation, but the outcomes have ripple effects that often extend far beyond individual products, case uses or companies, and ultimately, job seeker complaints become civil cases or class action lawsuits before becoming codified into case law, or sometimes, federal policy.

That’s when industry wide change really does come – and often, it’s an extinction level event (see: Zenefits, The Ladders, HiQ, etc).

And this week, the meteor finally hit, in the form of a proposed class action filing in California.

The filing alleges that talent technology stalwart Eightfold helped its customers – largely enterprise employers – compile and use “secret” evaluation reports on applicants without notifying them, first.

They were also accused of denying those same applicants the ability to view, or challenge, the content of those personalized profiles.

Candidates Are Consumers. Do They Have the Same Protections?

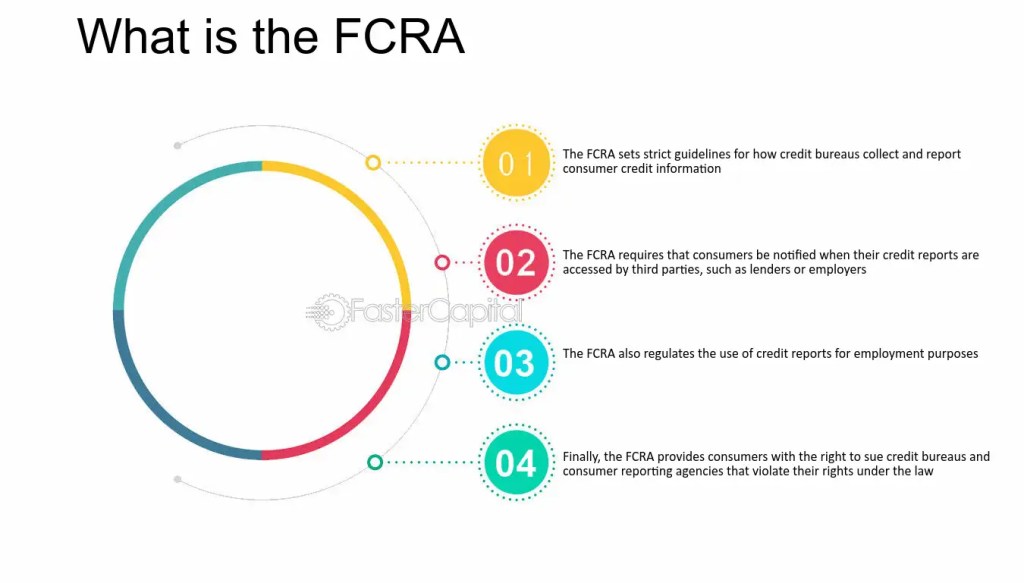

Those claims hinge on the idea that these agentic outputs amount to “consumer reports” for the purposes of making employment decisions, which drags Eightfold – and its partners, competitors and customers – into the arcane world of the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA), and related California consumer protection laws.

I know what you’re thinking. You’re probably like, “wait – isn’t FCRA the thing about background checks and credit reports?” Yup – nailed it. And if you’re wondering what the hell the FCRA has to do with leveraging AI for talent acquisition, well, that’s kind of the point.

The suit is basically arguing, and seemingly convincingly, that AI doesn’t get some magical exception that suddenly allows vendors to do dossier style assessments without the required disclosures and adverse action steps that the FRCA has already codified into case law.

The lawsuit, unlike so many similar actions taken by disgruntled job seekers or litigious competitors, doesn’t feel like a random ambush or some sort of unfortunate misunderstanding. It doesn’t feel like a petty complaint, nor a money grab, and there doesn’t seem to be any obvious motives for retribution in this quest for restitution.

Instead, this lawsuit feels like an inevitability for an industry that spent the last decade or so racing to build more sophisticated, spurious and scientifically suspect ways to screen and evaluate candidates as part of the prehire process – while simultaneously crossing their collective fingers that nobody would notice how opaque those systems and solutions had actually become.

Ironically, the most inscrutable of these vendors generally are the most vocal about their commitment to transparency and fairness (red flag, my dude).

Compliance theatre is a genre every buyer in the space is likely too familiar with already – even if most performances are pretty convincing, if we’re being honest. But these days, that theater has somehow gone off script and doing some crazy improv scene work instead. And if there’s one thing in life you can be sure of, it’s never trust an improv comedian. Or, you know, a software sales exec who can assure you that their AI hiring solution is 100% compliant, certified even.

Simply, no one knows what compliance in AI recruitment actually entails; there’s no real codified laws, regulation is spotty or non existent, and there is no legal precedent or case law to define the boundary between product innovation and compliance violation.

This field of law is rapidly emerging, and everyone’s kind of playing it by ear in the absence of any tangible guidance or guidelines. In the meantime, ignorance may be 90% of the law; but ignorance of those laws governing the usage of AI tools in hiring is absolute, since they’re about as real as LinkedIn’s analytics.

I say this as someone who has spent longer than he’d like to admit covering this insular industry with a healthy dose of cynicism, but also, with the hope that someday, we’d figure out the guardrails and get our collective act together, sooner or later.

And it turns out that “later” just arrived, wearing a gray suit and carrying an accordion folder full of filings, and asking uncomfortable questions about stuff like disclosure, consent, and whether or not AI generated hiring decisions are really all that different from the old school, prehire reporting requirements that are already regulated.

Plausible Deniability Isn’t A Feature

Look, if you work in TA, you can pretend that this lawsuit is an Eightfold problem, and if you’re not an Eightfold customer, then you probably dodged a bullet by choosing another vendor. That’s the thing: vendors always want you to believe that lawsuits are basically like food poisoning at a restaurant you didn’t eat at. No exposure, no worries.

Litigation can be unfortunate, even disruptive, but ultimately, if it’s not your technology provider, it’s not your issue. That’s a really comforting sentiment that’s also dead ass wrong.

This case isn’t about a single company, or even a single product, feature or function. It’s much bigger than that, believe it or not. It’s about what happens when AI in hiring becomes ubiquitous enough to attract serious scrutiny, and ultimately, what happens when vendors discover “we didn’t think that applied to us” or “our intent was completely benign,” or “everyone else is doing the same exact stuff,” are all really crappy defense strategies.

AI was the answer to some of the most persistent problems in talent acquisition, a silver bullet for better matching, more accurate performance predictions, cleaner funnels and more efficient, effective processes.They’d save us time and money, and do the dirty work for us while we finally were able to focus on higher value activities than, say, resume disposition or repetitive phone screens.

We got what we wished for. Now, we’ve got to settle our tab, and pay the inevitable costs that come when you choose convenience over privacy.

That’s the real story here.

This case – if it advances – is way, way bigger than Eightfold. It’s a warning sign for every TA leader that AI governance is far from settled, and any provider telling you that their solution is fully compliant, when in fact, it’s far too early to make that claim.

That’s where case law comes in.

When “AI Scoring” Looks Like Credit Reporting

The lawsuit contains descriptions of applicant profiles that include such factors as personality descriptors, education quality rankings, and predictions about performance, aptitude and fit.

The plaintiffs claim that candidates weren’t notified they were being evaluated against these criteria, weren’t permitted to access the data, and, crucially, weren’t given the chance to challenge or correct any errors. In other words, a blatant violation of each key consumer protection codified by the FRCA. If it applies, which is, of course, the critical question underlying the entire case.

FRCA compliance is like EEOC compliance- it’s not subtle or nuanced, really. Employers who leverage any kind of consumer reports in hiring have some mundane, but critical, legal responsibilities. They must get authorization from the candidate and provide pre-adverse action and adverse action notices when a report contributes to a negative hiring decision.

And FCRA compliance is not subtle. Employers using consumer reports in hiring generally have to do a few boring but legally meaningful things, like get proper authorization and provide pre-adverse action and adverse action notices when a report contributes to a negative hiring decision.

The FTC’s official guidance for employers explicitly outlines these seemingly simple steps, and unlike so much federal legislation, the FTC doesn’t try to obfuscate the law through inscrutable terminology or esoteric legal references.

They even supplement their guidance with a plain language explanation of the requisite notice process the act requires from employers; it’s basically “document your work, be transparent in your methadology, and give anyone subjected to consumer reports a chance to respond directly.”

The FTC’s guidance for employers is painfully clear about the steps. The FTC also has a plain-language explainer, called, appropriately, “Background Checks: What Employers Need to Know” that spells out the notification process in language that’s as easy to interpret as those OSHA posters in the break room:

“…when you run background checks through a company in the business of compiling background information, you must comply with the Fair Credit Reporting Act (FCRA).”

I’d encourage you to read the full six page, large font brochure in its entirety, but its guidance on FCRA compliance for employers is basically, “Get permission from the person before running a report, provide them with that report, and give them a chance to respond before taking adverse action.”

The FTC’s guidelines on disclosure requirements for advertising and marketing endorsements runs a cool 44 pages – compliance with the FCRA, by contrast, seems anything other than an onerous task. Compliance should, theoretically, at least, be as simple and straightforward as the statute itself.

If you’re a vendor, though, here’s the awkward part: if your product, AI or analog, uses structured assessments or product outputs designed to measure a candidate’s relative employability, it’s pretty likely that legally, the courts will treat them as “regulatory reports,” and subject them to the same legal standards as any background check or consumer report.

Sure, you can call this functionality “stack ranking,” “match scoring,” “predictive analytics,” or “talent inference,” but let’s just say that the regulators probably aren’t paying any attention to your branding or product positioning – and, unlike product marketers, have no patience for nuance or narrative.

The law is the law. And in this case, it couldn’t possibly be any more clear.

You Bought the AI. Now You Own the Consequences.

In the near term, this lawsuit will inevitably slow everything down for enterprise software vendors, as pending litigation is wont to do. This is ironic, of course – particularly since most AI tools and technologies were implemented explicitly to save time, expedite processes and optimize workflows.

As they say: be careful what you wish for, because if you thought processes were inefficient or requirements were overly cumbersome prior to implementing AI, just wait until you see the impact that this lawsuit is likely to have on your talent acquisition efforts.

First off, procurement is going to become much more involved in every purchasing decision HR makes, asking sharper questions and applying increased scrutiny (and likely, another layer of legal review) to every contract with every technology provider in the enterprise TA tech stack, from job boards to ERPs, along with every other point solution and integration partner that’s even tangentially leveraged for talent attraction or recruitment.

Privacy and information security teams, meanwhile, will start circling words like “profiling,” “inference,” “automated decisioning” or “training data,” while legal demands to know whether or not a vendor is functioning like a consumer reporting agency – a critical question that generally, only a ton of detailed documentation and even more detailed auditing can effectively answer.

They’ll also want to know how each technology approaches consent flows, what the adverse action workflows look like when the report is a LLM output rather than a .pdf background check, and how these platforms handle disparate impact, documentation requirements and decision defensibility.

For TA leaders, the practical effect should be pretty obvious: you’re about to start having to spend way more time defending your decisions around existing tools and technology – even the most minor point solution or SaaS seat licence will be subject to an excruciating level of scrutiny. So, that’s something to look forward to.

This is really just the icing on the compliance cake, piling on top of the existing regulatory patchwork of confusing, and often contradictory, local and state laws that are already squeezing AI hiring.

New York City’s notorious Local Law 144, for example, requires bias audits and candidate notifications for any “automated employment decision tools.” The city literally has an online complaint portal to aid enforcement, because humanity has no deeper psychological urge than the ability to file anonymous complaints when they’re pissed off or feeling some sort of way. This is why Glassdoor exists, after all.

One of the primary issues with using AI in talent acquisition is the dearth of associated federal rulings, regulations or case law precedents currently in place; the FCRA is the closest approximation, and that’s not even under the auspices of the Department of Labor. Increasingly, though, state and local rules are filling the void left by the federal vacuum.

AI related employment legislation, and associated litigation, has been proliferating at the state and local level, with new rules and regulations, across jurisdictions and use cases, seeming to push increased scrutiny – and enhanced liability – onto vendors and employers alike. Reuters explains this trend, and its implications pretty explicitly in this recent piece on state laws in AI on employment.

It’s pretty clear which way the winds are blowing, and the red flags and warning signs seem anything but subtle.

The short term prediction: AI usage in TA probably won’t noticeably slow down, even incrementally – in fact, adoption should continue to accelerate in the coming months. Recruiting organizations have already made their bets, and spent their budgets, on the promise and potential that AI hiring represents.

This isn’t going to stop because employers suddenly start erring on the side of ethics, or even because they’re particularly concerned about any hypothetical consequences or increased risk profiles.

The only thing that will slow down AI adoption in hiring has nothing to do with HR. But when legal and IT get involved, you ask permission, not forgiveness – and, increasingly, talent acquisition is likely to get neither from these key internal stakeholders.

When the Algorithm Gets Subpoenaed

Eightfold isn’t some bootstrapped, scrappy little startup that can hide behind the narrative of innovation, disruption, or even growing pains. The company is well established, sells into big employers, has gained some really impressive logos and received an even more impressive valuation during their last raise.

Their hockey stick revenue growth and success at scaling up, in fact, increasingly looks like a potential liaiblity rather than a salient selling point. The lawsuit specifically notes the technology’s widespread adoption among the Fortune 500, and how these companies systematically applied Eightfold to their hiring processes – a SOP that could well mean they’re SOL, TBH.

Near term, though, Eightfold will immediately shift their key business priorities from winning new logos to stabilizing their existing client base. That means less focus on topline growth and more on recurring revenues and renewals, which is a fundamentally different playbook.

This means:

- Customer reassurance: expect a blitz of client comms, contractual clarifications, and maybe product changes around disclosure, candidate access, data provenance, and retention.

- Sales friction: any enterprise deal in-flight now has a new slide in the risk deck titled “FCRA.”

- Operational Drag : think: legal fees, executive attention, and roadmap re-prioritization. Because nothing says “growth quarter” like depositions.

Could they settle quickly? Sure.

Most companies would rather just cut a check than become the test case that teaches an entire industry a new definition of “consumer report.”

But even a closed settlement, or optimally, a dismissal with prejudice (unlikely) doesn’t erase the core lesson here: processes matter more than platforms, a product’s output is way more important than its methodology or functionality, and ultimately, the courts don’t give a crap if a compliance violation was committed by artificial intelligence instead of natural stupidity or human error.

Eightfold will be the canary in the compliance coal mine for AI hiring – and perhaps finally teach the recruiting function a lesson that’s seemingly long overdue:

Technology alone will never solve the most persistent and pressing talent acquisition problems..Too often, though, it creates them. The existential risk here isn’t that Eightfold pays money. It’s that the case helps cement a precedent that applicant scoring vendors are subject to consumer-report-like obligations.

If courts start treating AI-generated applicant profiles as regulated reports, the industry shifts from “trust us, it’s AI” to “prove it, and document it.” That means:

- Transparency becomes product, not a blog post.

- Candidate access and dispute workflows become part of the platform.

- Data sourcing and model explainability become contractual commitments, not marketing phrases.

- Vendor liability becomes a real conversation, not a theoretical one.

Some vendors will adapt. Some will quietly change their language and hope nobody notices. And some will get acquired because it’s easier to merge into a bigger compliance machine than build one yourself.

Eightfold: The Roadmap to Redemption

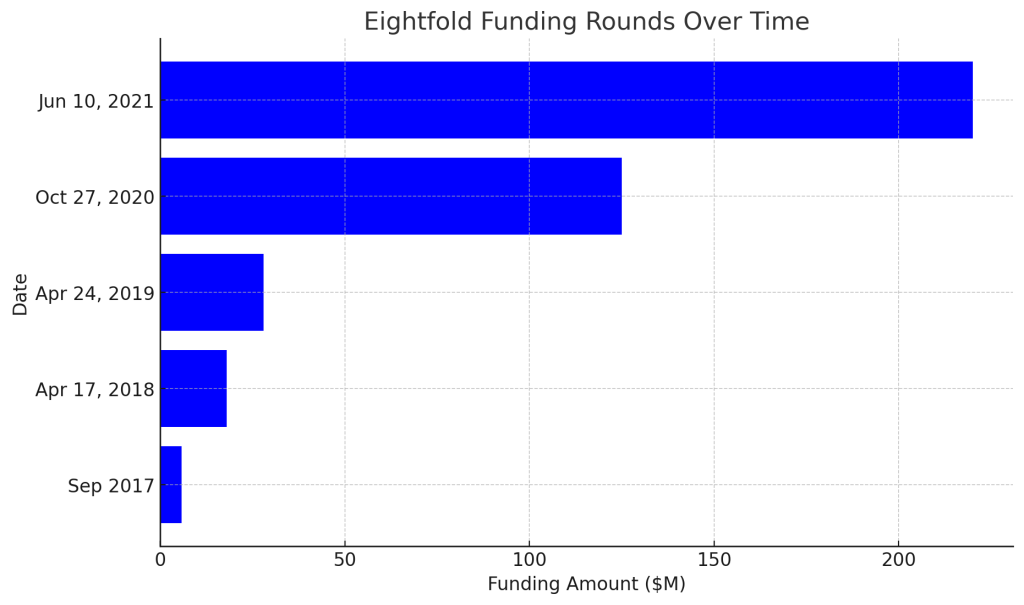

Eightfold raised big money in the boom years.

They announced a $220M Series E at a $2.1B valuation led by SoftBank Vision Fund 2 in 2021. That’s in their own announcement, so it’s not exactly gossip.Eightfold’s Series E post and TechCrunch’s coverage both put the stake in the ground.

But valuations from 2021 are like sourdough starters from 2020. Interesting history. Questionable relevance.

In 2026, the funding environment rewards two things: monstrous growth or defensible infrastructure. Everyone else gets “show me profitability” energy, plus a compliance tax.

Even in a hot AI market, capital has concentrated into fewer, larger bets, and investors are far more willing to punish anything that smells like regulatory exposure.

So what happens to Eightfold’s revenue growth and valuation trajectory?

- If they contain the issue (settlement, product updates, clear compliance posture), they likely keep most enterprise clients, but new growth becomes harder and slower. Sales cycles lengthen, and CFOs start asking whether “AI talent intelligence” is worth litigation-adjacent drama.

- If this turns into ongoing litigation and discovery that paints their practices as systematically opaque, the brand damage becomes durable. That’s when churn risk rises and expansion deals get shaky.

Either way, it’s not a tailwind for an IPO narrative. And it’s not the kind of story that makes late-stage investors eager to reprice you upward.

Now, here’s the part TA leaders hate: even if Eightfold is the defendant, employers aren’t insulated.

If your hiring workflow relies on third-party scoring, and candidates aren’t notified, and adverse-action style processes aren’t in place, you’re basically daring plaintiffs to widen the circle. And even when the lawsuit targets the vendor, employers still eat the operational mess: audits, candidate complaints, internal escalations, and PR risk.

Eightfold clients should be doing three things immediately. As in, like, yesterday:

- Map where AI outputs influence decisions (screening, ranking, rejection triggers).

- Demand clarity on data sources and candidate rights (access, correction, retention, opt-outs).

- Align the workflow to existing legislation and regulations, instead of going off of vibes or vendor guidance, using established frameworks like the FTC’s FCRA guidance referenced above.

There’s no need to panic. But you do need to realize that it’s not an Eightfold problem – if you’re a customer, it’s your problem now, too.

And you’ve got to be proactive about addressing that problem, rather than waiting for the vendor to find a resolution.

You Can Rebrand the Product, Not the Track Record

Now let’s talk about a big plot twist in this whole story, one that’s flown largely under the radar, even as scrutiny on Eightfold seemingly intensifies.

Here’s the thing: Eightfold isn’t the only work focused AI startup led by co-founders Ashutosh Garg and Varun Kacholia. Last fall, in fact, the pair launched a new product called Viven, positioned around “digital twins” for employees and enterprise knowledge, and it came out of stealth with $35M in seed funding, led by major venture names.

That’s not rumor, nor is it a takedown. It’s in TechCrunch; hell, Foundation Capital published their own thesis in their investment announcement, validating Vivian’s product-market fit and pedigree. Eightfold itself framed Vivien as an “independent company born from our innovation” in their funding announcement.

For the smartest guys in the room, this claim seems pretty stupid, and patently false. You don’t need an LLM to do some pattern recognition on this one.

And, of course, Josh Bersin completely validated this tool with a breathless post heavy with superlatives and suspiciously light on details, giving the product instant credibility and market validation, ostensibly in exchange for a fat check. Yeah, it’s all pretty gross, if we’re being honest – and while venture capitalists, “analysts” and founders continue to enrich themselves in an incestuous, if not entirely virtuous, cycle, the rest of us, sadly, are the ones who ultimately have to foot the bill.

Yeah, right.

In fairness, Viven is not a TA product, and the FCRA is not relevant to any of its purported outputs. But it’s still, objectively, pretty damned shady.. It’s being positioned as an enterprise OS for agentic AI, aimed at boosting workplace productivity and making institutional knowledge and internal information more accessible.

This means that, while it sits adjacent to the same sort of “people data” that fits squarely within Eightfold’s purview, it manages to avoid the risk – and radioactive compliance implications – associated with hiring decision making.

That’s a small difference, with big implications.

If, as is looking increasingly likely, AI usage in TA gets squeezed by disclosure requirements and reporting obligations, or the risk profile becomes greater than the potential ROI that these products generate, the smart money is that vendors simply shift from external talent acquisition to internal talent management.

Use cases like internal mobility, succession planning, productivity enablement and other enterprise specific talent management applications more or less remove any risks associated with consent, context or governance – or at least, make them way easier for organizations to manage and control.

Viven is perhaps the first of what may become a mass migration from talent acquisition to talent management for AI products; it’s essentially a hedge that AI at work can scale the fastest, and have the most significant impact, when it’s focused on helping employees do their jobs more efficiently and effectively, rather than deducing whether or not applicants are capable of doing those jobs in the first place.

It’s also a pretty convenient way to diversify Eightfold’s offerings: the same team, the same data, and the same infrastructure get slapped with a new name, a new platform and a new governance structure and boom – suddenly, they’ve got an entirely different profile when it comes to regulatory exposure and risk management.

The End of Risk-Free AI in Talent Acquisition

This lawsuit is a shot across the bow for the entire ecosystem of TA focused AI tools. The age of black box rankings and plausible deniability is abruptly ending; not because HR suddenly gained some sort of conscience, but because regulators finally noticed that slapping “AI” on a hiring decision does not magically supercede or bypass existing laws and regulations.

This lawsuit would represent a significant, even existential, business challenge for any VC backed startup, but if there’s one company that can survive this, it’s Eightfold. In fact, they might even come out of the other end of this with a stronger product and value proposition – learning a hard lesson in why compliance is more than marketing and messaging. Used properly, it’s a growth strategy, and, presumably, a competitive advantage.

If Eightfold outlasts this lawsuit, it will be because they can effectively explain how their LLM makes decisions, how bias is monitored, and provide solid proof that their governance model passes real compliance tests and legal scrutiny – claims that, as of now, are largely aspirational and completely unproven.

It’s not optimal to be the first AI player targeted with this sort of legal action – but if it can come out on the other side, it will be the first one whose product has proven defensibility. That’s a pretty salient selling tool when the competition is still trying to navigate the legal landscape and learn the rules of a game that Eightfold has already, effectively, won.

The bigger shift, though, transcends Eightfold. This isn’t about a single company, or a single lawsuit – it’s about accountability finally catching up to the AI Hype Cycle.

The era where TA leaders had carte blanche to buy and implement unproven “AI” tools and technologies explicitly to screen and assess candidates, effectively delegating responsibility to a third party vendor while treating transparency like it’s an optional add on rather than a foundational requirement is already over.

Guess what? When it comes to AI in TA, no matter how this lawsuit turns out, one thing should be crystal clear to HR leaders everywhere: you, and you alone, are responsible for outcomes. Your vendors don’t own AI, and they’re not accountable for its impact, good or bad, after implementation.

You own the outcome now, and the thing is, algorithms and LLMs don’t have to answer to your company’s general counsel or C Suite – HR does.

That’s going to be a change that takes some getting used to. The upside to all this is that this lawsuit essentially forces market maturity now that the grown ups (like lawyers and IT leaders) are paying attention. Tools and technologies improve when they have to let end users look under the hood, replacing black boxes with glass doors.

Teams get smarter, and more efficient, when they understand the tools they’re using, the implications behind that usage, and, ultimately, take a more concerted approach to adoption than the piecemeal approach that’s too common in TA today.

Finally, fairness in hiring increases when employers have to make defensible decisions that rely on human judgement, rather than outsourcing most hiring outcomes to an algorithm that they neither see or understand. None of this is going to come easy. And it probably won’t be cheap, either.

But this lawsuit, finally, represents real progress towards AI moving from vendor aspiration into recruiting reality – even if that change came wrapped up in a subpoena, it’s long one that’s unquestionably long overdue, too.

Thank you. Th