Still Crazy After All These Metrics: The Myth of Quality of Hire

Quality of hire is the kind of metric you trot out when you want everyone to believe you’ve unlocked the secrets of strategic recruiting without actually unlocking anything.

It’s performative, ambiguous and sounds like something you’d learn in business school, not something made up by product marketers. It looks great in a QBR. It sounds great during budget season. It gives executives that warm, fuzzy feeling that talent acquisition knows what it’s doing.

But behind the curtain, it’s no secret that no one really knows what they’re doing if their existential crisis led them to this random career path. We mostly do a pretty effective job of hiding that fact behind brand, bluster and buzzwords.

There’s a saying you can’t manage what you can’t measure, but the paradox of TA leadership is that when you have no actual clue what you’re supposed to be doing, you also have no idea what you’re supposed to be measuring, or what good looks like.

This makes choosing optics over outcomes an increasingly perilous decision for talent acquisition and recruiting leaders; the increasing focus on finally capturing the unicorn that is quantifying quality of hire proves that if recruiters disappear, it won’t be because of AI – it’ll be because of real stupidity.

If that sounds harsh, let’s start with the simple stuff, like ontology.

Here’s the thing: quality of hire has no standard definition. None. Even the foundational concept of “quality” is highly subjective, which is why they made multiple Avengers movies and the Traitors is one of the most watched shows on TV.

Just like there’s no accounting for taste, there’s no baseline for “quality.” It’s like the concept of relative value; quality, as an abstract theory, operates at the intersection of subconscious biases and budget availability.

Ask ten TA leaders what quality of hire means and you’ll get twelve answers (like I said, we kinda suck at math).

It’s more meaningless buzzword than measurable business outcome, kinda like agentic AI, only slightly more commoditized and conceptually, even more opaque and obtuse, if that’s even possible.

Quality of hire’s such a poorly defined metric that even the people who swear by it (mainly management consultants and product marketers) can’t tell you what it means.

It’s the recruiting equivalent of saying “synergy” in a board meeting. Sounds impressive, and means absolutely nothing, kind of like the phrase “top talent” or “employer value proposition.”

Of course, some TA leaders have finally stopped pretending this Quixotic quantification is real, and calling BS on this asinine, abstract and artificial concept. It’s management consultant speak for “we’ll know it when we see it” (coincidentally, porn also operates in this gray space), mostly because we’ve got no clue how to measure it.

It’s a vibe dressed up as a KPI, like company culture or candidate experience. But, we’re all supposed to treat that like strategy. Or at least a problem that can be solved with an overpriced SaaS subscription or spurious point solution.

Still, people cling to it, mainly analysts, growth marketers and HR Business Partners.

LinkedIn’s Global Talent Trends report ranks it as the top “most valuable metric” in recruiting (consider the source), even though fewer than half of companies say they measure it in a way that actually influences decisions. The other half, presumably, are lying.

And let’s not forget, SHRM claims a bad hire can cost up to three times the role’s salary – and they’ve been saying that for years. How do they arrive at this outcome? Is there a formula to accurately correlate “bad hires” with annualized compensation?

It doesn’t actually exist. But like so much SHRM content, the sentiment is always more important than the statistics. Plus, the fact that Johnny C Taylor makes $3.5M a year (compared to the 8M in annual losses indicated in the most recent SHRM financials) should prove that even the industry’s most august trade association has no clue about calculating the cost of a bad hire.

Here’s hoping it comes with a tote bag.

Kodachrome Promises in a Spreadsheet World

Even if you land on a definition of “quality of hire” that feels reasonable, or in any way logical or self-evident, you likely lack either accurate data, analytics abilities or self-awareness (or, most often, some combination thereof).

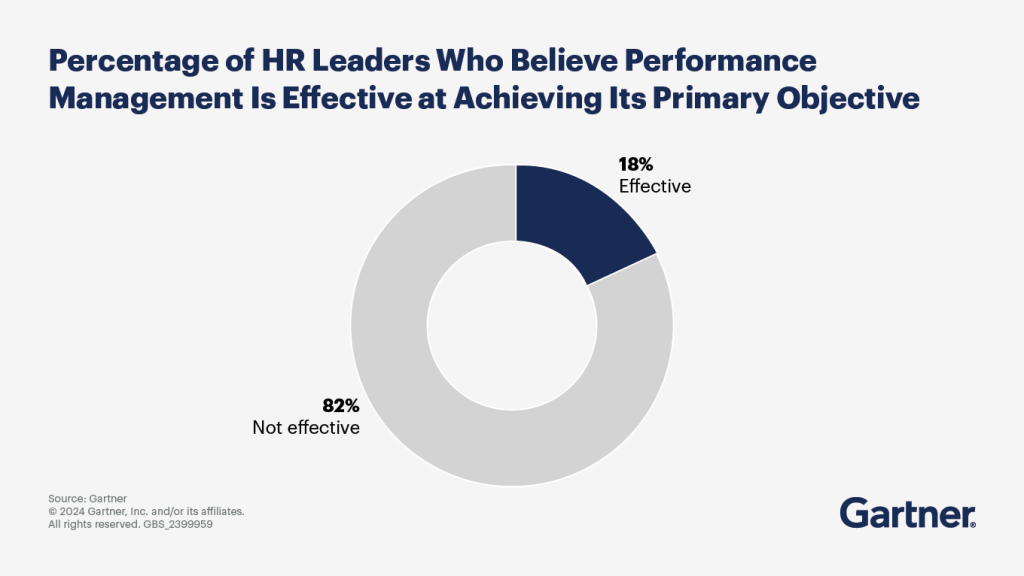

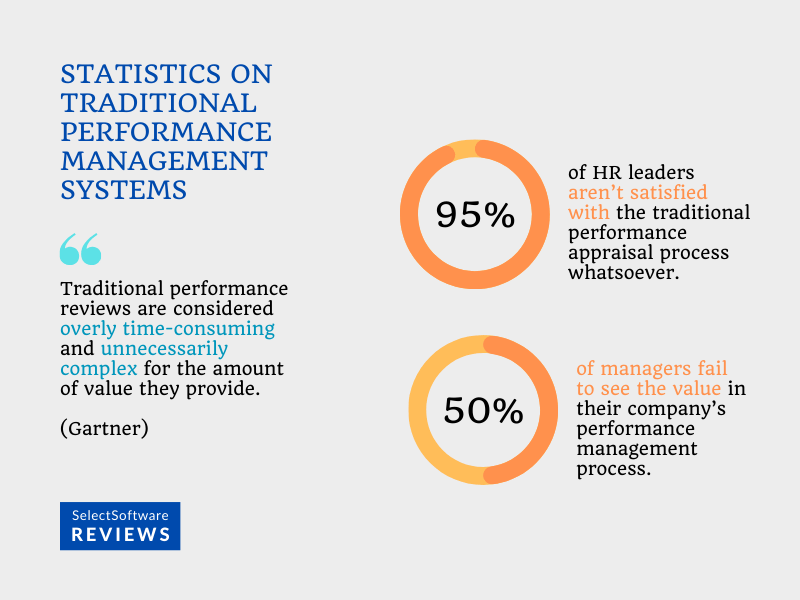

The thought that any organization can accurately forecast the relative performance of future employees is pure fiction or lazy product marketing, considering we lack the capability to measure or manage even historical performance data from our existing workforce – a remedial exercise, by comparison.

Look at performance reviews. Executives and CHROs swear by them. The performance management vertical prints cash, realizing approximately $4B a year in aggregate spend by US companies alone. It’s a mature category, firmly entrenched into best practices and business processes at pretty much every employer out there.

What’s rarely mentioned, though, is that performance reviews aren’t a measurement of capability, but instead, likeability. Gallup, for example, found that about 60% of data related to performance variance comes from the manager, not the employee.

This means performance management is not an indicator of how well an employee manages their performance, but instead, how well they manage the perception of that performance.

In other words, we throw billions of dollars a year down the drain to create the illusion of transparency and structure around performance, or at least some sort of defensibility around decisions that create potential compliance issues or raise HR’s risk profile.

Performance reviews determine who gets promoted, who gets a raise, who gets in the President’s Club and who goes on a PIP – and because there’s self-reported data and structured feedback involved, we trust that these reviews are indicative of anything more than the arbitrary preferences of a hiring manager with a spreadsheet.

They’re not, and are about as accurate a predictor of job performance as Presidential approval ratings (Lincoln still holds the historical low, for what its worth) – but then again, measuring popular sentiment or personal opinion is an exercise in futility (or a really expensive management consulting project).

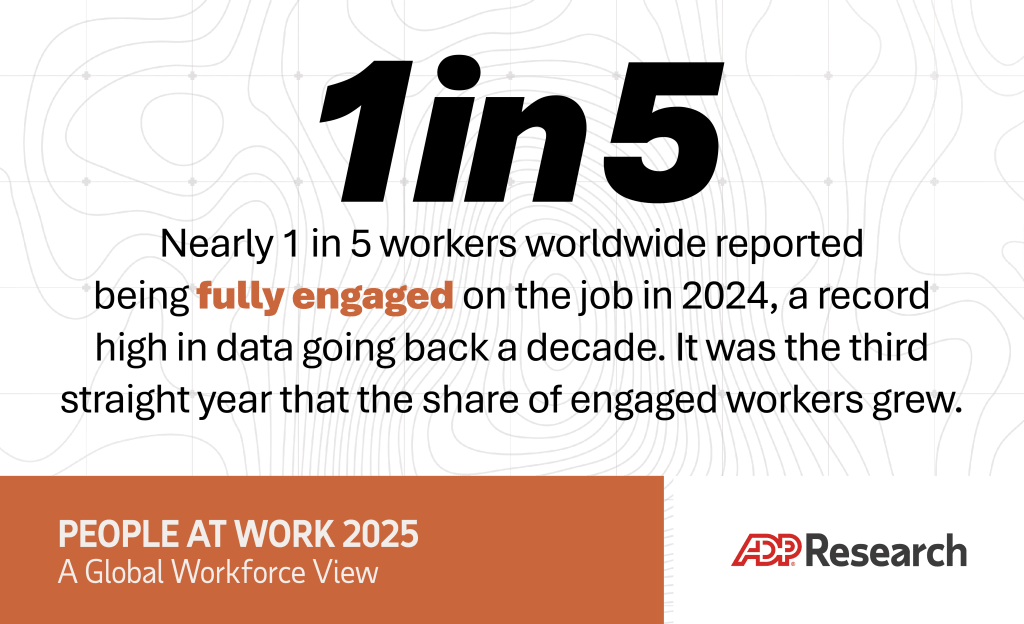

Let’s look at one of TA’s other professional peccadillos: retention. Retention is good; churn is bad. But here’s the thing: tenure and performance aren’t positively correlated, either. In fact, the opposite seems to be true – the highest performers are generally the biggest flight risks, for obvious reasons.

“Regrettable attrition” is what happens when you lose A players. Reductions in force is what happens when you lose everyone else. It’s a distinction that’s very rarely based on reliable data.

And since we only hire “top talent,” it’s often those with the longest tenures whose jobs tend to be the most tenuous. If someone sticks around the same employer, in the same job, with the same responsibilities and essentially the same compensation, that’s not indicative of quality. It’s indicative of comfort.

Tenure shouldn’t be confused with value – and lifers aren’t always leaders. So conflating quality of hire with retention, as many organizations are wont to do, is pretty much pointless.

Similarly, if we define quality by hiring manager satisfaction or eNPS (barf), then culture fit and interpersonal chemistry should be the sole dimensions for driving hiring decisions. Vibes, however, do not create value. No matter how much your recruitment marketing agency wants to convince you otherwise.

Performance, retention, relative engagement and manager satisfaction are all pretty standard dimensions for building quality of hire benchmarks and baselines, but this is a fundamental fallacy.

Quality of hire is a flawed metric, but it’s an even worse selection strategy. It’s akin to choosing a steakhouse based on Yelp reviews of vegan restaurants, or choosing which final candidate gets the offer based on the quality of their reference checks – and just as asinine.

Slip Slidin’ Away: Leaders and Laggards

Here’s the problem.

Quality of hire isn’t a leading indicator of employee potential or a predictor of future performance; by the time you can quantify this concept with any degree of accuracy, it’s already too late.

You only find out that the new hire everyone was so excited about kind of sucks when they’ve spent weeks – or months – on the job, and by the time the quality of that hire comes into question, the damage is already done. By then, the budget and resources have been spent, the team is already falling behind on the work, and everyone but the bad hire is suddenly a flight risk.

At best, quality of hire is useful as a postmortem, but knowing the cause of death doesn’t change the fact that, well, they’re dead. And the autopsy results (or exit interviews, if you like) almost never change recruiting processes, job descriptions, search strategies or selection criteria.

If you can’t accurately measure source of hire, cost per hire or even time to fill – and let’s be honest, most employers lack even the data for those most basic baselines. We still need to learn basic arithmetic before we waste any more time trying to pick up differential calculus on the fly.

50 Ways to Build Your Benchmarks

If you want to make better decisions, stop relying on a lagging indicator. Start using real-time data that’s prescriptive, not predictive, and help you realistically improve recruitment efficacy and hiring outcomes before it’s too late to fix things.

Here are four every talent pro should know:

Get off the ramp, Stan

Measure time to productivity. It’s more useful than waiting a year to see if someone’s “high quality.” Gartner reports that faster ramp times predict long-term success.

The faster they get up to speed, the more likely they are to stay and succeed.

You don’t need to be right, Mike

Start tracking hiring decision accuracy. Did the candidate who nailed the interview actually perform well? Did your structured interview questions predict anything real?

If not, the problem’s probably not the hire. It’s the process.

Hop off the bus, Gus

Look at your 30, 60 and 90 day attrition rate like you were a contingent recruiter. By the time performance reviews come around, it’s probably too late; the Work Institute found that more than a third of turnover happens in year one.

The fact of the matter, though, is that most of that early attrition comes from mismatched expectations. From employer brands that are more aspirational than accurate, to job descriptions that in no way describe the actual job, this churn is not only regrettable, but entirely avoidable.

These retention challenges are, in fact, unresolved recruiting problems. Start fixing this, first.

Make a new plan, Jan

Track hiring manager accountability. Gartner says that workforce performance jumps 20 percent when managers’ performance reviews or variable compensation (like bonuses or stock grants) is tied to hiring success.

If managers can ghost candidates, ignore scorecards, and still blame TA for bad hires, then it’s because you’ve convinced the org that QoH is a reflection of recruiting efficacy rather than hiring manager ineptitude, broken processes or internal misalignment.

A Bridge Over Troubled Metrics

Sure, keep quality of hire in your reporting if you want – but don’t expect it to drive any real impact or tangible changes. It’s a narrative tool, not a performance metric.

If you’re still chasing better ways to measure your team’s impact, then keep going. It might not work, but sometimes, that’s not the point.

Talent acquisition is long overdue for better metrics, better tools, and better answers. So quality counts, but only relative to your job performance and professional development.

So keep experimenting. Keep pushing. And never stop looking for ways to quantify your impact on the business or the bottom line.

Build better benchmarks. Find better tools. Focus on talent intelligence, not artificial intelligence – for real. Stop pretending vibes are data. And finally admit that quality of hire is a marketing myth, not a talent acquisition metric.

The good news? You don’t need to keep telling it. You just need to start writing a better one.