Latin American Workers: The Future of U.S. Labor Markets

For the better part of the last thirty years, give or take, globalization wasn’t treated as an abstract economic theory, but rather, as a deeply entrenched, systemic and intractable part of how the world fundamentally works.

The path towards a global hegemony in which distributed workforces, borderless businesses and decentralized teams was progress that we largely took for granted; globalization was, not too long ago, kind of like gravity: a natural phenomena that was inescapable, inevitable, and occasionally, a little inconvenient, too. It wasn’t something you argued about; it was something you adapted to.

Let’s just say, things have changed – and now, borders are not seen as administrative, arbitrary lines on a map, but tangible, and powerful, policy instruments best wielded bluntly. Multinational trade is no longer about achieving efficiency and economy of scale; it’s about achieving leverage and economic advantages.

Here in the United States, policy and politics have swung back to isolationism and protectionism; nationalism is no longer a fringe and kind of archaic worldview, but instead, is seen as a pragmatic response to the purported “foreign” influences that pose an existential threat to the lives, and livelihoods, of every American.

First World Problems, Third World Solutions

While one could reasonably argue that putative tariffs, flat wage growth, months of consumer price increases and a precipitous decline in purchasing power are the most probable culprits for our economic malaise, the villain of this geopolitical potboiler is much more straightforward and simple.

It’s all the fault of illegal – and mostly criminal – immigrants, a societal scourge much more menacing than, say, the erosion of constitutional protections, the rising threat of authoritarianism or the shift from open markets to outright oligarchy.

This has led to the increasingly aggressive immigration policies – and consequent enforcement tactics – that disproportionately impact workers and their families, the overwhelming majority of whom have no criminal record, pay taxes and work for poor wages in even poorer conditions.

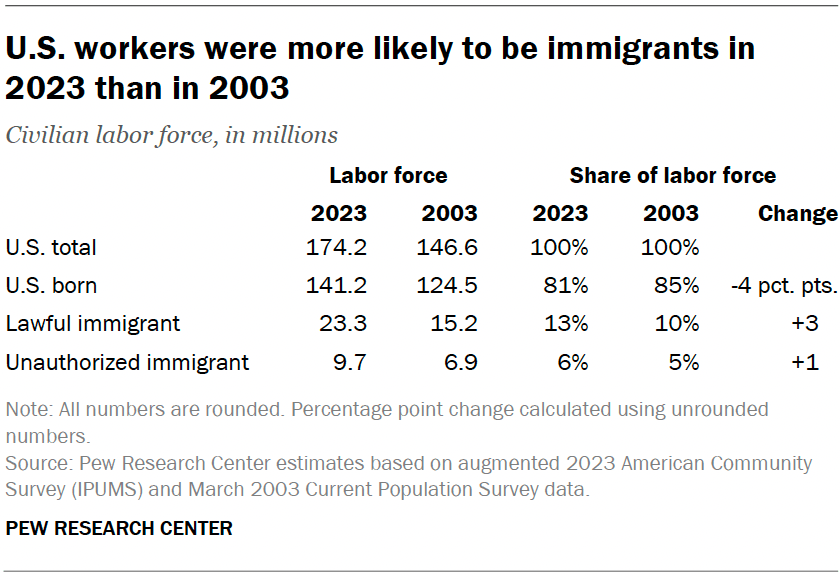

Workers who have historically propped up the US economy, in other words, also represent the most imminent danger, and impending threat, to our economic prosperity in the future. It’s a logical contradiction, but so too is the fact that more federal money is allocated to immigration enforcement annually than into job training, apprenticeships and placement programs for US workers (by a factor of around 5x, for what it’s worth).

This isn’t a temporary correction or a political mood swing; it’s a structural shift that’s reshaping labor markets, talent flows and economic growth at the exact moment when demographic data pretty clearly shows that over the next decade, it’s unlikely the US will have enough domestic workers left to sustain the current economy, much less drive even incremental annual growth.

And sorry – not even AI, the societal silver bullet – can reverse this troubling trend. If anything, it’s already pushing the workforce perilously close to the edge of that dangerous demographic cliff.

They Took Our Jobs (Because We Wouldn’t)

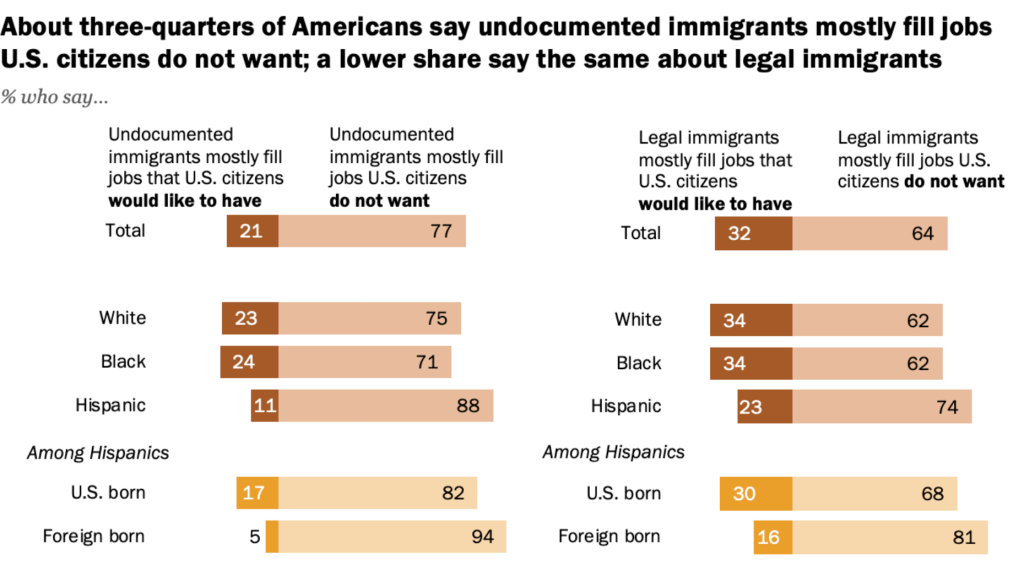

While it’s almost a cliche at this point, there is a growing body of statistical evidence that shows that these immigrants, irrespective of legal status, mostly take jobs that US citizens don’t want.

A recent poll from the Pew Research Center shows that nearly three out of four Americans agree that domestic workers can’t (or won’t) perform the sorts of work in which immigrants are disproportionally represented, like agriculture, construction and hospitality – sectors in which immigrants represent over 25% of all workers, despite representing just over 10% of active workforce participants, in BLS parlance.

When three out of four Americans can agree on anything these days, that’s tantamount to a universal consensus in terms of public polling data. But here’s the interesting twist: when Pew broke down this sentiment by demography, a startling 93% of Hispanic respondents agreed that, in fact, immigrants perform work that US citizens simply don’t want (and would summarily refuse, even if otherwise unemployed).

This improbably high polling result, however, is largely based on lived experience. When politicians and pundits talk about the threat “immigrants” in general, but undocumented immigrants in particular, represent to public safety and national security, the subtext is clear.

They’re implicitly talking about Hispanic immigrants, as opposed to, say, Ukrainian refugees or the tens of thousands of Balkans who similarly sought refuge from an indeterminable, and bloody, war just a generation ago (or, presumably, Slovenian immigrants, which include the NBA’s premier player, the current First Lady, and more professional models per capita than any other sovereign state).

Latin American Workers and the American Economy: An Uneven Exchange Rate

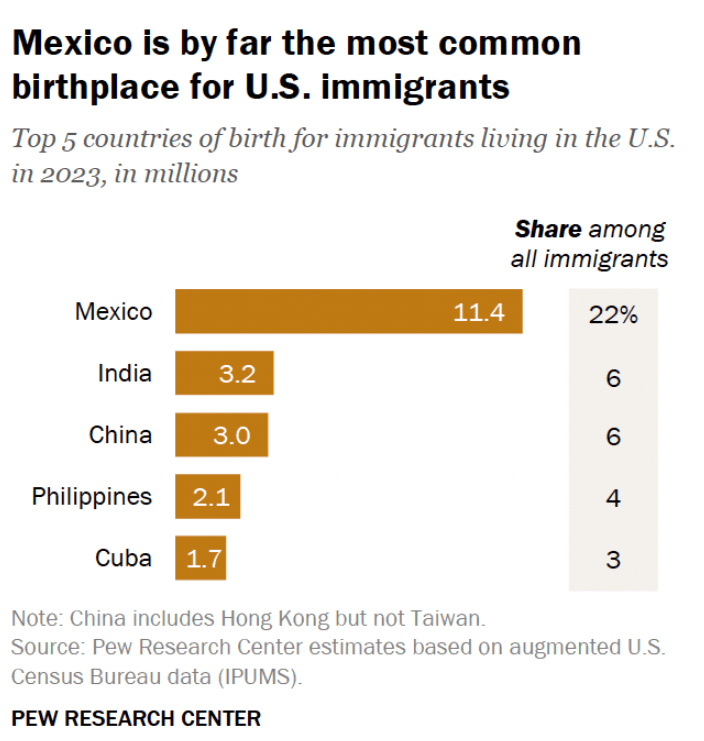

Statistically speaking, around 52% of all immigrant residing in the US, irrespective of status, were born in Latin America – that’s nearly 27 million people, or around three times as many workforce participants as the total number of K-12 school teachers, first responders and licensed healthcare providers currently working in the US – combined.

All of these professions, while essential to our collective quest for life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness, are already suffering from acute staffing shortages and a lack of available talent. Forced mass deportations are unlikely to replenish these critical professional pipelines anytime soon, which is unfortunate, given the increasing restrictions on H1-B and other visa programs explicitly offered to offset domestic skill gaps and talent shortages.

The future of work doesn’t look very bright, at least for American citizens. But, assuming that immigration enforcement succeeds in removing even a fraction of Latin American immigrants, it should prove to be a boon for those developing nations whose most valuable export product (and most precious resource) is human capital.

Of course, most Latin American migrants are economic refugees, rather than unwanted criminals, drug smugglers and other miscellaneous “bad hombres.” Latin Americans who immigrate outside the region are often highly educated and highly skilled. They don’t lack talent – they largely lack access to jobs, and often have extremely limited opportunities (and intense competition) that enable any existence beyond subsistence.

In the meantime, half of the “thought leaders” on LinkedIn – and far too many US employers and hiring managers – still treat Latin America like the discount aisle at a TJ Maxx. For “global” TA leaders, LATAM is basically a bargain bin of cheap, offshore labor – or a compliance and continuity risk that they can’t quite define, but worry about quite a bit over $14 lattes during DEIB planning sesssions.

Immigration is apparently excluded from inclusion – and diversity is valued, as long as that’s entirely limited to native English speakers whose “lived experience” and “diversity of thought” happened exclusively within the borders of the United States (missionary, study abroad trips or temporary work assignments notwithstanding).

The reality? Latin America is where the future of work isn’t some noxious marketing buzzword or a trite naming convention for content marketing assets like webinars and white papers. That’s because the future of work isn’t happening in developed nations with advanced economies, like the US, Canada, or EMEA (minus the MEA part, as a mea culpa).

In Latin America, the future of work is happening right now. It’s not an abstract theory; it’s operational reality. We’re talking about demonstrably faster digital adoption, a median age that makes America look like an assisted living community by comparison, and the cost and production pressures inherent to near-shoring that force leaders to make decisions quickly, workers to adapt with minimal notice and even less training, and companies that can change business models in less time than it takes most American senior managers and executive leaders to “circle back.”

What happens in Latin America doesn’t stay in Latin America; it’s the stress test for what the workforce of tomorrow looks like, happening right now, in real time.

And there’s perhaps no better place to get a front row seat for a sneak peek into the future of work than Mexico City – the largest city in the Americas by population, the largest local economy of any Spanish speaking city in the world and, most importantly, the commercial and business hub of a country that accounts for fully 22% of all immigrants currently working in the United States.

The Future of Talent Starts in Mexico City

What’s happening in Mexico doesn’t stay in Mexico – the emerging trends, tech and talent emerging from south of the border can have profound long term implications for the US, American workers and the US economy. Exhibit A: Texas.

I’m not attending this week’s Future Talent Forum to hear “thought leaders” follow familiar scripts; I’m not there to learn about the implications of artificial intelligence, nor do I care about best practices in employer branding, or how to build a business case for whatever market challenge Josh Bersin manufactured and monetized this quarter. And I certainly could give two shits about, say, industry politics or insider gossip, nor do I care to discuss your latest LinkedIn post or the latest Chad and Cheese hot take.

I’m going because if you actually want to see the future of work, you need to stand somewhere the old assumptions no longer hold.I’m not going to Mexico to collect buzzwords, compare prompt frameworks, or nod politely while someone rebrands basic math as a “new workforce paradigm.” I’ve had enough conference espresso and AI Mad Libs to last a lifetime.

Mexico is where global labor theory collides with reality. Where closed US borders are quietly rerouting opportunity. Where talent markets are growing instead of freezing, scaling instead of hoarding, and learning how to operate under real constraints instead of infinite venture money and slide decks. It’s a place where hiring still has consequences, technology has to earn its keep, and workforce strategy is shaped by demographics and economics rather than LinkedIn consensus.

That’s why I keep coming back to Future of Talent Council events. The conversations are sharper and the speakers have actually built things, rather than simply sell them. The audience at FTC events aren’t auditioning for influence; they’re trying to understand what’s happening next, and what to do about it before the rest of the market catches on.

If the US is busy debating whether the old system can be patched, Mexico is busy building around it.

I’m going to see what’s really going on in what’s emerging as the world’s fastest growing, and most lucrative, market for offshore and outsourced labor, how talent technology works under severe operational and resource constraints, and how closed borders are opening up unprecedented opportunities for Latin American workers.

I want to see what happens in hiring in a market that’s undergoing explosive economic and population growth, has made exponential gains over the past decade alone in terms of per capita income, relative purchasing power and quality of life – in other words, the exact opposite of what we’ve been seeing in the United States.

Viva La Revolución.

Part 1 of a 2 part series on the future of talent acquisition in Latin America